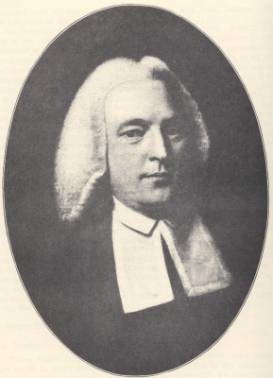

JONATHAN SEWALL.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

OF MASSACHUSETTS.

The family of Sewall is traced to two

brothers, Henry, and William Sewall, both Mayors of Coventry, England, Henry

Sewall born about 1544, was a Linen Draper, Alderman of Coventry, Mayor in 1589

and 1606. Died 1628, aged 84. Buried in St. Michael’s Church, Coventry.

Married Margaret, eldest daughter of Avery

Grazebrook.

Their son Henry Sewall, emigrated to New

England in 1634[1]. He came

over “out of dislike to the English Hierarchy[2]”

and settled at Newbury. He died at Rowley in 1657, aged 86 years. Married Anne

Hunt. They brought with them their son, Henry Sewall[3],

born in Coventry, in 1614, died in 1700, aged 86. Married Jane Dummer in

Newbury, 1646. He went back to England and resided for some years at Warwick.

In 1659 he returned to New England, “his rents at Newbury coming to very little

when remitted to England.” His son Stephen was born at Badesly, England, in

1657. He came to New England in 1661, settled at Salem and was a Major in the

Indian wars. He died in 1725. Married Margaret, daughter of Rev. Jonathan

Mitchell of Cambridge in 1682. They had an only son Jonathan, who was a

merchant at Boston. He married Mary, sister of Edward Payne, of Boston. They

had a son,

JUDGE

JONATHAN SEWALL, the

subject of this notice. He was born at Boston in 1728. Graduated at Harvard

College in 1748, and was a teacher at Salem till 1756. He married Esther,

daughter of Edmund Quincy, Esq.. of Braintree, afterwards of Boston, and sister

of Dorothy Quincy, wife of Governor Hancock, and of Elizabeth Quincy, wife of

Samuel Sewall, of Boston, the father of Samuel Sewall, Chief Justice of

Massachusetts. Jonathan Sewall studied law with Judge Chambers Russell, of

Lincoln, commenced practice in his profession at Charlestown. He was an able

and successful lawyer. He was Solicitor General, and his eloquence is

represented as having been soft, smooth and insinuating, which gave him as much

power over a jury as a lawyer ought ever to possess. At the death of Jeremy

Gridley, he was appointed Attorney-General of Massachusetts, September, 1767.

In 1768 he was appointed Judge of Admiralty for Nova Scotia. He went there

twice in that capacity, and remained but a short period.

He was a gentleman and a scholar. He

possessed a lively wit, a brilliant imagination, great subtlety of reasoning

and an insinuating eloquence.

He was an intimate friend of John Adams,

they studied together in Judge Russell’s office, and afterwards, while

attending court, they lived together, frequently slept in the same chamber, and

often in the same bed, and besides the two young men were in constant

correspondence.

He attempted to dissuade John Adams from

attending the first Continental Congress, and it was in reply to his

arguments, and as they walked on the Great Hill at Portland, that Adams used

the memorable words, used so often afterwards in 1861 when the ordinance of

secession was passed: “The die is now cast, I have now passed the Rubicon; sink

or swim, live or die, survive or perish with my country, is my unalterable

determination.” They parted, and met no more until 1788. Adams, the Minister of

the new republic at the Court of St. James, and the eloquent and gifted Sewall,

true to the Empire, met in London, Adams laying aside all etiquette made a

visit to his old friend and countryman, he said, “I ordered my servant to

announce John Adams, I was instantly admitted, and both of us forgetting that

we had ever been enemies, embraced each other as cordially as ever. I had two

hours conversation with him in a most delightful freedom, upon a multitude of

subjects.” In the course of the interview, Mr. Sewall remarked that he had

existed for the sake of his two children, that he had spared no pains or

expense in their education and that he was going to Nova Scotia in hope of

making some provision for them.

In 1774, he was an Addresser of Governor

Hutchinson, and in September of that year his elegant home in Cambridge (which

he rented from John Vassal, afterwards Washington’s head-quarters, since

occupied by the poet Longfellow) was attacked by the mob and much injured. He

fled to Boston to escape from the fury of the disunionists. He had ably

vindicated the characters of Governors Bernard, Hutchinson and Oliver, he was

esteemed an able writer, and a staunch loyalist. He was proscribed in the

Conspirators Act of 1779. He resided chiefly in Bristol till 1788, for the

education of his children, then he removed to St. John’s, N. B., having been

appointed Judge of Admiralty for Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. He immediately

entered upon the duties of his office, which he held till his death, which

occurred September 26, 1796, at the age of sixty-eight. His widow survived him,

and removed to Montreal, where she died January 21, 1810.

JONATHAN SEWALL, son of the aforesaid, was born at Cambridge, 1766,

was educated at Bristol, England, and afterwards resided at Quebec, where he

occupied the offices of Solicitor and Attorney General and Judge of the Vice

Admiralty Court, until r8o8, when he was appointed Chief Justice of Lower Canada,

which he resigned in 1838. For many years he was President of the Executive

Council, and Speaker of the Legislative Council.

In 1832 he received the degree of Doctor of

Law from Harvard College. He died at Quebec in 1840, aged seventy-three. His son

Stephen[4]

was Solicitor General of the same Province in 1810 and resided in Montreal. He

died there of Asiatic cholera in the summer of 1832.

SAMUEL SEWALL, son of Henry Sewall and

brother of Major Stephen Sewall, was the first chief justice of Massachusetts.

This was the famous Sewall that sat in judgment upon the witches and afterwards

repented it, who refused to sell an inch of his broad acres to the hated

Episcopalians to build a church upon, who was one of the richest, most astute,

sagacious, scholarly, bigoted[5]

and influential men of his day, who has left us in his Diary a transcript

almost vivid in its conscientious faithfulness of that old time life, where he

tells us of the courts he held, the drams he drank, the sermons he heard, the

petty affairs of his own household and neighborhood, and where he advised with

the governor touching matters of life and death. He married Hannah, the only

child of John Hull, the mintmaster, who it is said gave her, on her marriage, a

settlement in pine tree shillings equal to her weight. Hull owned a large farm

of 350 acres in Longwood, Brookline, which descended to his son-in-law, and was

known afterwards as Sewall’s Farm.

Samuel Sewall, son of the aforesaid,

married Rebecca Dudley, a daughter of the governor. His son, Henry Sewall, born

in 1719, died in 1771, was a gentleman much respected, and a lawyer of

prominence. His son,

SAMUEL SEWALL, the subject of this article, was born at Brookline,

December 31, 1745. Graduated at Harvard College in 1761. He studied law and

settled in Boston. His name occurs among the barristers and attorneys who

addressed Governor Hutchinson in 1774, and in the Banishment and Proscription

Act in 1778, when his large estate which he had inherited from his ancestors,

was confiscated. He went to England, and in 1776 was a member of the Loyalist

Club, London. Two years later he was at Sidmouth, a “bathing town of mud walls

and thatched roofs.” In 1780 he was living in Bristol, and on the 19th

of June amused himself loyally celebrating Clinton’s success at Charleston in

the discharge of a two-pounder in a private garden, and three days later was

shot at by a highwayman and narrowly escaped with his life. Early in 1782 he

was at Taunton, and at Sidmouth. He died at London, after one day’s confinement

to his room, May 6th, 1811, aged fifty-six years. He was unmarried.

LIST OF CONFISCATED ESTATES BELONGING TO

SAMUEL SEWALL

IN SUFFOLK COUNTY AND TO WHOM SOLD.

To Edward

Kitchen, Wolcott, July 19, 1782; Lib. 135, fol. 113; Land 263 A, 1 qr., in

Brookline, Thomas Aspinwall E.; marsh road to Charles River N.E.; Charles River

N.; Thomas Gardner and Moses Griggs S. and S.W.; Solomon Hill S. and S.E.

——Land, 16 A. 3 qr., and half of house in Brookline on Sherburn Road and the

marsh lane, bounded by Capt. Cook, Samuel Craft and Elisha Gardner.

To John Heath,

Nov. 12, 1782; Lib. 136, fol. 102; Land and buildings in Brookline. 9 A. 33 r.,

Sherburn Road S.E..; a town way N.E.; Mr. Aker N.W.; a town way S.W.—32 A. 3

r., Daniel White and the pound S.W.; road and Joseph Williams S.E.; Joshua

Boylston and William Hyslop N.E.; Sherburn Road N.W.——18 A. 2 qr. 5 r., Samuel

White N.W.; John Dean S.W. and S.; a town way S.E.; said Dean N.E.; S. E. and

S.; said town way E.; road N.E.—59 A. 3 qr. 4 r., Benjamin White and Dr.

Winchester N.E.; Sarah Sharp S.W.; Samuel White and heirs of Justice White

S.E.; Benjamin White N.E.; S.E. and N.E.; Sherburn Road N.E.—23 A. 3 qr. 33 r.,

Ebenezer Crafts and Caleb Gardner N.W.; said Gardner and Benjamin White S.W.;

Moses White S.E.; Benjamin White and Moses White N.E.; Moses White S.E.; a town

way N.E.—3 A. 28 r., Ebenezer Craft SW.; S.E. and N.E.; the County line N.W.——8

A. 1 qr., 31 r., Daniel White N.W.; the County line S.W.; David Cook S.E.;

heirs of Ebenezer Davis N.E.—5 A. 2 qr. 38 r., said Craft N.W.; saw mill meadow

W.; William Heath S. and S.E.; Benjamin White and William Hammon N.E.—7 A. 2

qr., 32 r., Edward K. Walcott S. and W.; Benjamin White S.; William Acker S.E.;

John Child E.; Charles River N.; Joseph Adams and Daniel White W.—4 A. 26 r.,

Moses White W., Esquire White, Ebenezer Craft and a creek S.; Nehemiah Davis

and heirs of Caleb Denny S.E.; the marsh road N.

To John

Molineux, William Moilneux, Aug. 11, 1783; Lib. 139, fol. 153; Land and

buildings in Boston, Newbury St. W.; Daniel Crosby, John Solely and heirs of

Benjamin Church deceased S.; land late of Frederick William Geyer E.; Thomas

Fair-weather, Sampson Reed, John Homands and Edward Hollowday N.; said Sewall

W.; N.; W. and N.

To John McLane,

Dec. 18, 1783; Lib. 140, fol. 207; Land and buildings in Boston, Newbury St.

W.; said Sewall S.; E.; S. and E.; Edward Hollowday N.

THOMAS ROBIE.

William and Elizabeth Robie were

inhabitants of Boston as early as 1689, when their son Thomas was born on March

20th of that year. He graduated at Harvard College in 1708, and died

in 1729. He was tutor, librarian, and Fellow of the college. Be published an

account of a remarkble eclipse of the sun on Nov. 27, 1772, also in the Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society, papers on the Alkaline Salts, and the

Venom of Spiders (1720-24). The following extract from the diary of President

Leverett shows the estimation in which he was held. “It ought to be remembered

that Mr. Robie was no small honor to Harvard College by his mathematical

performances, and by his correspondence thereupon with Mr. Durham and other

learned persons in those studies abroad.” In mathematics and natural philosophy

he was said to have no equal in New England.

His mother was Elizabeth Taylor, daughter

of James Taylor, long treasurer of the Province. He went to Salem and

established himself in the practice of physic, and married a daughter of Major

Stephen Sewall.

THOMAS ROBIE, of Marblehead, was a son of the preceding Dr. Robie.

He was a merchant, and married a daughter of the Rev. Simon Bradstreet, who was

the great grandson of Gov. Bradstreet, called the Nestor of New England. Mr.

Robie was a staunch loyalist, was an Addresser of Gov. Hutchinson, and thus

brought upon himself and family the ire of the Revolutionists. They were

obliged to leave the town and take refuge in Nova Scotia. Crowds of people

collected on the wharf to witness their departure, and many irritating and

insulting remarks were addressed to them concerning their Tory principles, and

their conduct towards the Whigs. Provoked beyond endurance by these insulting

taunts, Mrs. Robie retorted, as she seated herself in the boat that was to

convey her to the ship: “I hope that I shall live to return, find this wicked

rebellion crushed and see the streets of Marblehead run with rebel blood.” The

effect of this remark was electrical among the Revolutionists and only her sex

prevented them from doing her person injury. But there were other loyalists in

Marblehead who, if not so demonstrative, were not less sincere in this opinion.

With fortitude and silence they bore the taunts and insults to which they were

subjected, honestly believing that their friends and neighbors were engaged in

a treasonable rebellion against their lawful sovereign.

Mr. Robie first went to Halifax, but

afterwards to London, Feb. 5, 1776. He passed his time of exile mostly in

Halifax, where one of his daughters married Jonathan Stearns, Esq., another

refugee; another was married to Joseph Sewall, Esq., late treasurer of Massachusetts.

After the war was over some of the refugees

attempted to return to their former homes. During the month of April, 1783, the

town was thrown into a state of the greatest excitement by the return of

Stephen Blaney, one of the loyalists. Rumors were prevalent that other refugees

were also about to return, and on April 24 a town meeting was held, when it was

voted that “All refugees who made their appearance in town were to be given six

hours notice to leave, and any who remained beyond that time were to be taken

into custody and shipped to the nearest port of Great Britain.” Late one

afternoon after this action of the town a vessel from the provinces arrived in

the harbor. It was soon ascertained that the detested Robie family were on

board, and, as the news spread through the town, the wharves were crowded with

angry people, threatening vengeance upon them if they attempted to land. The

dreadful wish uttered by Mrs. Robie at her departure still rankled in the minds

of the people and they determined to give the Robies a significant reception.

So great was the excitement that it was feared by many of the influential

citizens that the unfortunate exiles might be injured and perhaps lose their

lives at the hands of the infuriated populace. During the night, however, a

party of gentlemen went on board of the schooner and removed them to a place of

safety. They were landed in a distant part of the town and secreted for several

days in a house belonging to one of the gentlemen. In the meantime urgent appeals

were made to the magnaminity of the turbulent populace, and the excitement

subsided.

Mr. Robie went into business again in a

limited extent, and died at Salem about 1812, well esteemed and respected. The

large brick mansion house of Thomas Robie is situated on Washington street,

near the head of Darling street, Marblehead.

SAMUEL BRADSTREET ROBIE, son of the above, of Halifax, was

appointed solicitor-general of Nova Scotia in 1815, speaker of the house of of

assembly in 1817, 1819-20, member of the council in 1824, and master of the

rolls in 1825, and died at that city January, 1858, in his eighty-eighth year.

SAMUEL QUINCY

SOLICITOR GENERAL

Edmund Quincy, the first of the name in New

England, landed at Boston on the 4th of September, 1633. He came

from Achurch in Northamptonshire, where he owned some landed estate. That he

was a man of substance may be inferred from his bringing six servants with him,

and that he was a man of weight among the founders of the new commonwealth

appears from his election as a representative of the town of Boston in the

first General Court ever held in Massachusetts Bay. He was also the first named

on the committee appointed by the town to assess and raise the sum necessary to

extinguish the title of Mr. Blackstone to the peninsula on which the city

stands. He bought of Chickatabut, Sachem of the Massachusetts tribe of Indians,

a tract of land at Mount Wollaston, confirmed to him by the Town of Boston,

1636, a portion of which is yet in the family.

Edmund Quincy died the year after making

this purchase, in 1637, at the age of 33. He left a son Edmund and a daughter

Judith. The son lived, in the main, a private life on the estate in Braintree.

He was a magistrate and a representative of his town in the General Court, and

Lieutenant-Colonel of the Suffolk Regiment.

Point Judith was named after his daughter.

She married John Hull, who, when Massachusetts Bay assumed the prerogative of

coining money, was her mint-master, and made a large fortune in the office,

before Charles II put a stop to that infringement of the charter. There is a

tradition that, when he married his daughter to Samuel Sewall, afterwards Chief

Justice, he gave her for her dowry, her weight in pine-tree shillings. From

this marriage has sprung the eminent family of the Sewalls, which has given

three Chief Justices to Massachusetts[6]

and one to Canada[7], and has

been distinguished in every generation by the talents and virtues of its

members.

Lieutenant-Colonel Quincy, who was a child

when brought to New England, died in 1698, aged seventy years, having had two

sons, Daniel and Edmund.

Daniel died during his father’s lifetime,

leaving an only son John, who graduated at Cambridge in 1708, and was a

prominent public man in the Colony for nearly half a century. He was a Councillor,

and for many years Speaker of the Lower House.

He died in 1767, at the time of the birth

of his great-grandson, John Quincy Adams, who therefore received the name which

he has made illustrious. Edmund, the second son, graduated in 1699, and was also in the public service almost all his life, as a

magistrate, a Councillor, and one of the Justices of the Supreme Court. He was

also colonel of the Suffolk Regiment, at that time a very important command,

since the coun ty of Suffolk then, and long after, included what is now County

of Nor folk, as well as the town of Boston. In 1737, the General Court

selected him as their agent to lay the claims of the Colony before the home

government, in the matter of the disputed boundary between Massachusetts Bay and

New Hampshire.

He died, however, very soon after his

arrival in London, February 23, 1737, of the smallpox, which he had taken by

inoculation. He was buried in Bunhill Fields, where a monument was erected to

him by the General Court, which also made a grant of land of a thousand acres

in the town of Lennox to his family, in further recognition of his public

services.

Judge Edmund Quincy had two sons, Edmund

and Josiah.

The first named, who graduated at Cambridge

in 1722, lived

a private life at Braintree and in Boston.

One of his daughters married John Hancock,

the first signer of the Declaration of Independence, and afterwards Governor of

Massachusetts. Josiah was born in 1709, and took his first degree in 1728. He

accompanied his father to London in 1737, and afterwards visited England and the

Continent more than once.

For some years he was engaged in commerce

and ship-building in Boston, and when about forty years of age he retired from

business and removed to Braintree, where he lived for thirty years the life of

a country gentleman, occupying himself with the duties of a county magistrate,

and amusing himself with field sports. Game of all sorts abounded, in those

days in the woods and along the shore, and marvellous stories have come down,

by tradition, of his feats with gun and rod. He was Colonel of the Suffolk

Regiment, as his father had been before him; he was also Commissioner to

Pennsylvania during the old French war to ask the help of that Colony in an

attack which Massachusetts Bay had planned upon Crown Point. He succeeded in

his mission by the help of Doctor Franklin.

Colonel Josiah Quincy, by his first

marriage, had three sons, Edmund, Samuel, Josiah, and one daughter, Hannah. His

first wife was Hannah Sturgis, daughter of Johns Sturgis, one of his Majesty’s

Council, of Yarmouth. His eldest son, Edmund, graduated in 1752, after which he became a merchant in Boston. He was in England in 1760 for the purpose of establishing

mercantile correspondences. He died at sea in 1768, on his return from a voyage

for his health to the West Indies.

The youngest son of Colonel Josiah Quincy

bore his name, and was therefore known to his contemporaries, and takes his

place in history, as Josiah Quincy, Junior, he having died before his father,

he was born February 23, 1744, and graduated at Harvard

College, 1763. He studied law with Oxenbridge Thacher, one of the principal

lawyers of that day, and succeeded to his practice at his death, which took

place about the time he himself was called to the bar. He took a high rank at

once in his profession, although his attention to its demands was continually

interrupted by the stormy agitation in men’s minds and passions, which preceded

and announced the Revolution, and which he actively promoted by his writings

and public speeches. On the 5th of March, the day of the so called

“Boston Massacre” he was selected, together with John Adams, by Captain

Preston, who was accused of having given the word of command to the soldiers

that fired on the mob, to conduct his defence and that of his men, they having

been committed for trial for murder. At tha moment of fierce excitement, it

demanded personal and moral courage to perform this duty. His own father wrote

him a letter of stern an strong remonstrance against his undertaking the

defence of “those criminals charged with the murder of their fellow citizens,”

exclaiming, with, passionate emphasis “Good God Is it possible? I wilt not believe it!”

Mr. Quincy in his reply, reminded his

father of the obligations his professional oath laid him under, to give legal

counsel and assistance to those accused of a crime, but not proved to be guilty

of it; adding: “I dare affirm that you and this whole people will one day

rejoice that I be came an advocate for the aforesaid criminals, charged with

the mur der of our fellow citizens. To inquire my duty and to do it, is my aim.” He did his duty and his

prophecy soon came to pass.

There is no more honorable passage in the

history of New Engand than the one which records the trial and acquittal of

Captain Preston and his men, in the midst of the passionate excitements of that

time, by a jury of the town maddened to a rage but a few months before by the

blood of her citizens shed in her streets.

In 1774

he went to England, partly for his health, which had suffered much from

his intense professional and political activities, and also as a confidential

agent of the Revolutionary party to consult and advise with the friends of

America there. His presence in London coming as he did at a most critical moment

excited the notice of the ministerial party, as well as of the opposition. The

Earl of Hillsborough denounced him, together with Dr. Franklin, in the House of

Lords, “as men walking the streets of London who ought to be in Newgate or

Tyburn.” The precise results of his communications with the English Whigs can

never be known. They were important enough, however, to make his English

friends urgent for his immediate return to America, because he could give

information which could not safely be committed to writing. His health had

failed seriously during the latter months of his residence in England, and his

physicians strongly advised against his taking a winter voyage.

His sense of public duty, however, overbore

all personal considera tions, and he set sail on the 16th of March,

1775, and died off Gloucester, Massachusetts, on the 20th of April.

The citizens of Gloucester buried him with

all honor in their graveyard; after the siege of Boston, he was removed and

placed in a vault in the burying ground in Braintree. Josiah Quincy was barely

thirty-one years of age when he thus died.

His father, Colonel Quincy lived on at

Braintree during the whole of the war. He died on March 3rd, 1784.

His passion for field sports remained in

full force till the end, for his death was occasioned by exposure to the

winter’s cold, sitting upon a cake of ice, watching for wild ducks, when he was

in his seventy-fifth year.

SAMUEL

QUINCY, the

subject of this memoir, was the second son of Colonel Josiah Quincy, and the

brother of Josiah, Junior, and Edmund. He was born in that part of Braintree

now Quincy. April 23, 1735. He graduated at Harvard College in

1754, and studied law with Benjamin Pratt.

Endowed with fine talents, Mr. Quincy

became eminent in the profession of the law, and succeeded Jonathan Sewall as

Solicitor-General of Massachusetts. He was the intimate friend of many of the

most distinguished men of that period, among whom was John Adams. They were

admitted to the bar on the same day, Nov. 6, 1758.

As Solicitor for the Crown, he was engaged

with Robert Treat Paine in the memorable trial of Capt. Preston, and the

soldiers in 1770; his brother was opposed to him on that occasion, and both

reversed their party sympathies in their professional position. It was plain to

all sagacious observers of the signs of the times, that the storm of civil war

was gathering fast; and it was sure first to burst over Boston. It was a time

of stern agitation, and profound anxieties. In their emotion Mr. Quincy and his

wife shared deeply, and passionately. The shadows of public and private

calamity were already beginning to steal over that once happy home. The evils

of the present and the uncertainties of the future bore heavily on their

prosperity. The fierce passions which were soon to break out into revolutionary

violence and mob rule, had already begun to separate families, to divide

friends, and to break up society. Samuel Quincy was a Loyalist and remained

true to his oath of office, wherein he swore to support the government. His

father and brother were revolutionists; as previously stated his brother died

on shipboard off Gloucester, seven days after the hostilities had commenced at

Lexington, and when his father saw from his house on Quincy Bay, the fleet drop

down the harbor, after the evacuation of Boston on March 17, I776, it must have

been with feelings of sorrow that the stout hearted old man saw the vessels

bear away his only surviving son, never to return again[8].

Such partings were common griefs then, as ever in civil wars, the bitterest

perhaps that wait upon that cruelest of calamities.

Samuel Quincy was an addressor of Governor

Hutchinson, and a staunch Loyalist. His wife, the sister of Henry Hill, Esq.,

of Boston, was not pleased with her husband’s course in the politics of the

times, and he became a Loyalist against her advice, and when he left Boston, a

refugee, she preferred to remain with her brother, and never met her husband

again. The following letter written to his brother by Mr. Quincy, during the

siege of Boston, will explain his position at that time.

Samuel Quincy was appointed comptroller of

the customs in Antigua in 1779. His

wife died in 1782, and he married again while in Antigua to Mrs. M.A. Chadwell,

widow of {Hon.} Abraham Chadwell. In

1789, Mr. Quincy embarked for England, accompanied by his wife. The restoration

of his health was the object of the voyage, but the effort was unsuccessful; he

died at sea, within sight of the English coast. His remains were carried to

England, and interred on Bristol hill. His widow immediately reem barked for

the West Indies, but her voyage was tempestuous. Grief for the loss of her

husband, to whom she was strongly attached, and suffering from the storm her

vessel encountered, terminated her life on her homeward passage.

It was a singular coincidence that two of

Mr. Quincy’s brothers died at sea, as he did on shipboard, Edmund, the eldest

and Josiah, the youngest brother.

Samuel Quincy had two sons: Samuel, a

graduate of Harvard College in 1782, who was an attorney-at-law in Lenox,

Mass., where he died in January, 1816, leaving a son Samuel. His second son,

Josiah, became an eminent counselor-at-law of Romney, N. H., and President of

the Senate of that State.

Mr. Samuel Quincy was proscribed and

banished and his property confiscated.

|

|

|

Samuel Quincy, Solicitor General of Massachusetts. Born at Braintree, Massachusetts April 23,

1735. Died at sea in 1789. |